You log into Twitter, that dark platform for your daily doom scroll, when you notice a tweet by a U.S. congressman using “unconventional” language. Their language is atypical of political promotion and portrays speech that is more personal and alive, even appropriate as it relates to the situation. Unfortunately, you make the mistake of lingering a bit, and your punishment is a catalogued barrage of people, some of them political opponents of varying positions (this is how many spend their free time), chastising the OP for their unexpected usage. The threads run down the gamut of insulting flavors, some patronizing the OP for daring to use “inappropriate” language, some repeat racist syllogisms, and all of them ignore the content of the OP’s tweet for contrived linguistic grievances. All in all, everyone’s time has been wasted, and you can blame the linguistic vigilantes for it.

Linguistic vigilantism was the subject of Dr. Dylan Dryer’s talk a couple of weeks ago for WRD’s quarterly Speaker Series. To him, the phenomenon puts on display linguistic oppression at the micro level, informed by dominant language ideology and generated through common social situations. Whether it’s on Facebook or in a classroom, these vigilantes are hanging around waiting to assume power in the smallest of occasions.

If you think this kind of language policing is perhaps not worth looking into, Dryer disagrees, thinking of it instead as an opportunity for insight. “Leaving language vigilantism untheorized means missing opportunities to find more productive outlets for people’s curiosity for language,” he said. “It’s better to see the curiosity as natural, not the policing. People do notice and are interested in language variation; we just haven’t given them anything to do with that curiosity.”

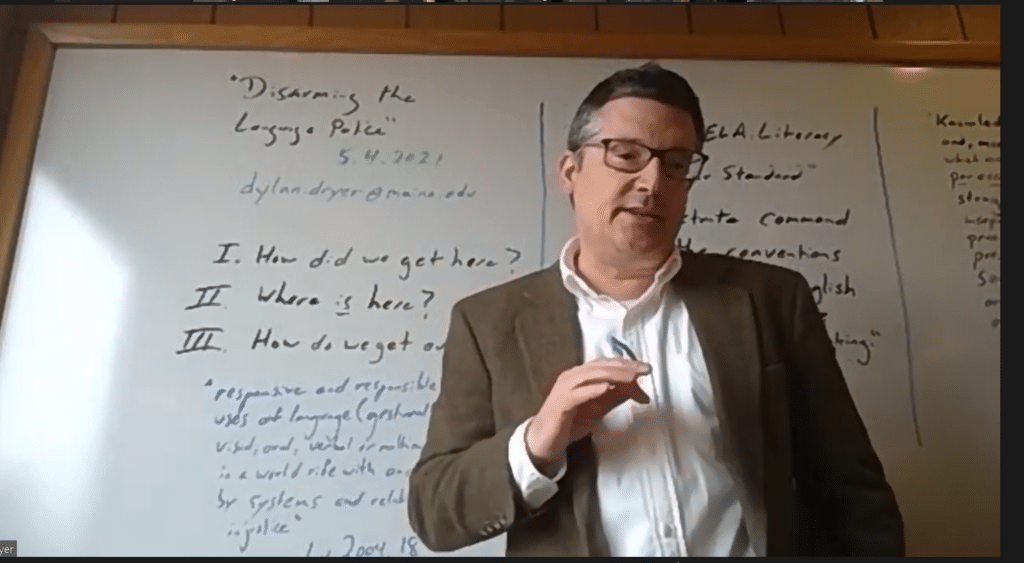

Dryer ran his talk similar to a classroom lecture, albeit with a Zoom aesthetic. A few times throughout, Dryer sent the audience out into breakout rooms to discuss certain prompts as they related to linguistic policing, prompts like “What are the most influential and widespread ‘commonsense’ notions of language that you encounter?” and “Share an experience of having your language policed” (Ironically, it simulated the real experience of breakout rooms in the Zoom classroom, with some groups engaged and others emitting an awkward silence). He immersed his audience into the subject, resulting in real relatable experiences with language to arise during the speech.

Dryer posits that at some point in the 20th c. the knowledge of English became more about loyalty to English. The old mission statement of English education, to “Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking,” continues to be enforced today starting at Kindergarten and permeating it infinitely through school till, as Dryer asserts, is baked in by late high school. This ideological assumption instills a view where any language usage that isn’t “standard,” whatever that actually means, is erroneous in nature, the unspoken implication being that it is lesser.

“It’s less official language policy than behaviors that I’m interested in today,” said Dryer. “Less language police than language vigilantes; here, I’m thinking particularly of the ‘I’m silently judging your grammar’ t-shirt, the verb tense bullies in online forums, the permission that people give themselves to disguise other biases in critiques of other people’s language, and the broad anxiety that is preyed upon by organizations like Grammarly.”

It is here that linguistic vigilantes come into being, but many of us get away from this line of thinking. What keeps someone loyal to this view of language? Dryer posits that it is due to phenomenological primitives, or tiny intuitive explanations of the world that work in terms of offering local explanatory power for what we see but inhibit development in grasping larger order concepts. Put more simply by Dryer, “It’s an evil threshold concept- it actually blocks your understanding of larger or other concepts.”

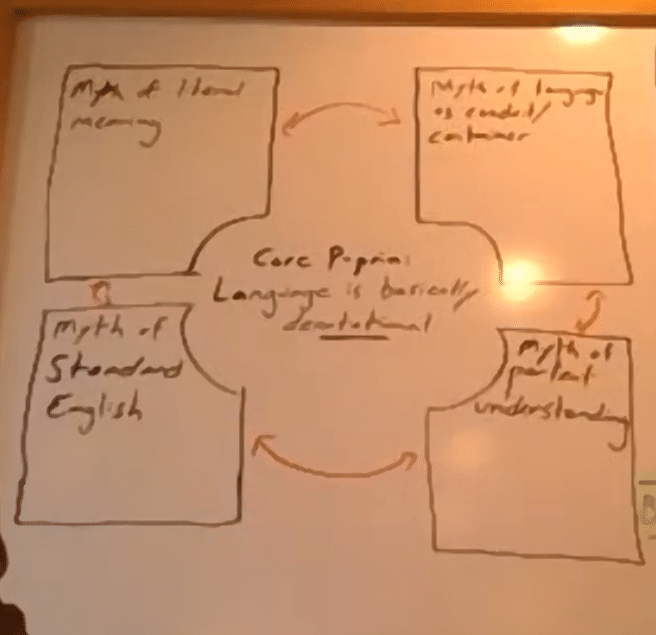

How this forms for linguistic vigilantes is through a complex of myths or assumptions of language, swerling around the premise that language is ultimately denotational, or that it is the sum of its functions, mainly in giving names to things. The myths that arise from this core belief are best represented in four cyclical pillars that support and “prove” one another. In summation, English and language by proxy is for the vigilante a tool that just is; to them, it is historically disconnected, socially isolated, and monologic; there is only one voice, and you are contemptible if you do not use that voice.

Dryer closed with some questions and comments from his audience, but one of his last ideas that he left his audience with was that writing and English teachers are brokers of language. The power in that position allows for considerations of linguistic ideology, that teachers have the power to influence how people view their own language. That power can be used to promote a freer and more curious view of language.

“By virtue of our credentials, we are positioned and expected to be language brokers. Our service is not to adjudicate language but to help people see that they don’t have to be afraid.”