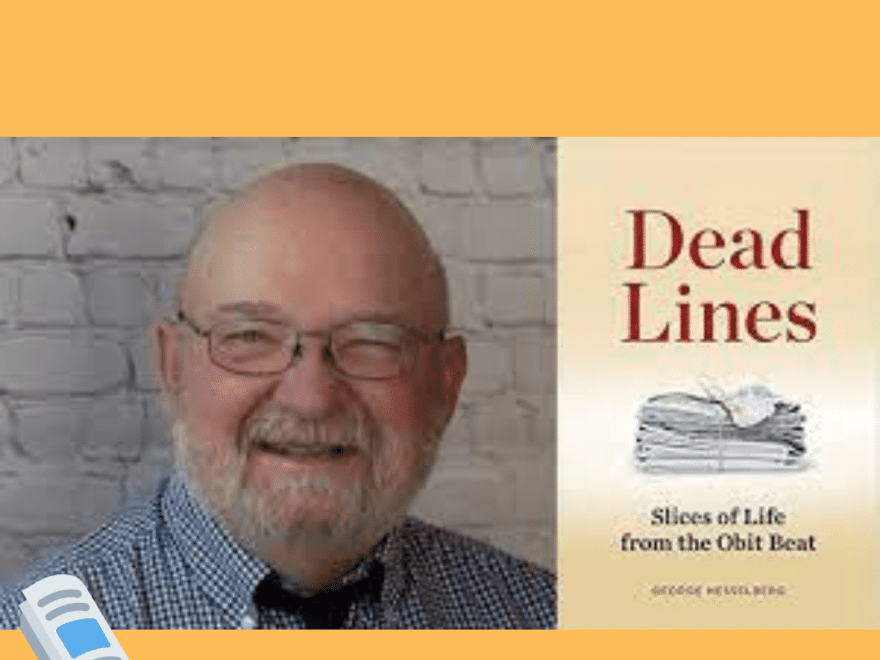

We interviewed GA Amanda Finn’s former colleague from Wisconsin State Journal George Hesselberg. Hesselberg worked as a police reporter for 10 years, columnist for 18 years and worked nearly every beat in his 42 years at the State Journal. He retired a few years ago and his book Dead Lines came out three weeks ago. The book covers fascinating stories that came from decades of covering the obit and public safety police beats.

We asked George about how things have changed over the span of his long career. He replied “things have changed as far as the rhetoric goes….police realize ‘no comment’ isn’t going to get them very far.” He also said that his last couple years as a journalist required him to pay more attention to police budgets, and that people were more hard-pressed to know about the paper trail involved in police funding.

We wanted George to share the role of rhetoric in his reporting work. The first thing he told us was something to the effect of “the goal of journalism is truth, but that truth is conveyed through the rhetoric of an individual journalist’s perspective.” He explained that when it comes to police or crime reporting, it can be easy for journalists to get caught up in legal or police jargon. He explained the initial incident reporting process to us; after a crime incident, a police departments issue an initial report, before any charges have been brought forward. This report is approved by police supervisors and communicated to the press by department spokespeople and media professionals from the police department. The role of the reporter in the early timeline of a breaking story is to figure out the most extensive truth around the crime by getting information other reporters aren’t getting and use insider sources. This can sometimes be difficult because secrecy is often important for authorities to apprehend criminals. Crime reporters must answer an important question for themselves: “What should go public?” They then adjust their rhetoric to fit the truth they have discovered.

With the dwindling down of newsrooms this question has become more the journalist’s responsibility than ever. Hesselberg noted that oversight in newspaper publication has shifted drastically, as there used to be several levels of oversight including the editor, copyeditor, news editor, city editor, etc. But several of those “correction elements” or “truth-finding elements” have been eliminated as positions in newsrooms.

Often statements released by the police can be hard to understand and filled with euphemisms, Hesselberg explained. Euphemisms, like metaphor, hyperbole and circumlocution, allow for noncommittal language that is careful not to direct a claim before a verdict is reached. In printed media, Hesselberg mentioned, there is time to gather information needed for the report. Hesselberg mentioned one tactic used by police departments is the “small incident strategy,” where spokespeople presenting a bigger, more critical incident will use the same, offhand language used to cover a smaller incident to downplay the severity of the situation. In some mediums like radio, incidents are reported as soon as the story breaks, so the language in these initial reports is often even handed and unrevealing. George shared that the best way to communicate the truth when using initial reports with little detail provided is to keep it simple, or “just stop using adjectives” so that communication comes across clear and direct instead of confusing or overly detailed. George mentioned that it takes a lot of time to sift through the bureaucratic language of crime reporting, noting “the worst thing you can do is write a correction…cops remember that.” Thus, deciphering official reports is a slow, careful one that is often also under the pressure of some deadline.

Crime reporters are frequently faced with rhetorical dilemmas involving tone, vocabulary, and reference in how they write about local crime, since police departments often vette the information released in the initial report. Rhetorically they must be both factually accurate as well as clear to the reader which can be difficult when working through police jargon. This is one reason why being at a scene with your “feet on the ground” is the best way to be a crime reporter. Being on scene gives a reporter much more to work with than just a press release. That’s also why it is important for reporters to ask questions, especially following press conferences when all of the reporters present are being given the same information. Following up on matters with an information professional, who is expected to be available to clarify meanings of “bureaucratese” language used in reports also helps curtail assumption-making, particularly about breaking crime news.

As a closing remark, Hesselberg contrasted semantics, or “bureaucratese”, with rhetoric in his work. He told us “rhetorical remarks made in police reports are often framed or blamed as semantics, when really they are part of an informed rhetorical decision.”

There are a lot of conversations going on around the role of racist/classist/ableist rhetoric in the role of police/crime beats in the United States. If you are interested in following NiemanLabs’ endeavor to defund crime reporting check out their website:niemanlab.org/2020/12/defund-the-crime-beat.