Last Monday, WRD hosted its quarterly speaker series with Dr. Cedric Burrows from Marquette University. He talked about his recently published book Rhetorical Crossover: The Black Presence in White Culture, which covers the diverging racial narratives told respectively by white and Black cultures through American history.

Burrows is an assistant professor of English at Marquette University, his subjects of study including African American writing, rhetoric and culture. His research over the last few years has been on historical narratives told over time about racial experiences, how those narratives have been coded by the dominant structures, and how black Americans have responded with their own narratives. This research culminated in his new, where he points to the emergence as creating dual narratives operating on different levels of space and time. As Burrows puts it, two societies, two narratives.

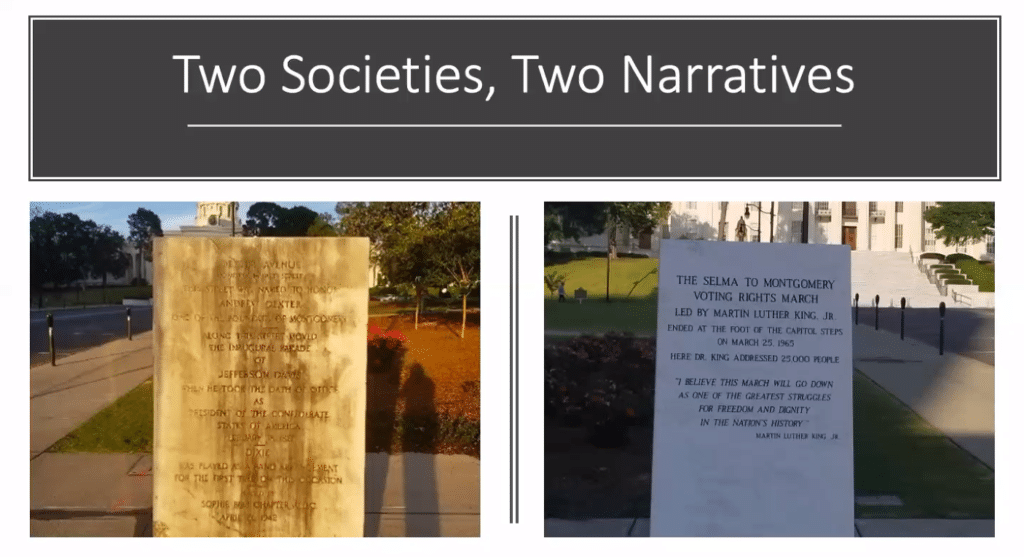

“I was watching the 60 minutes one day,” said Burrows, “and Oprah was talking about the lynching memorial site that was about to open in spring. So the second week that it was open I went down to Alabama and spent a week down there. I went to the lynch memorial site and then also went down Dexter avenue, and what really captured my attention were two columns that actually stand across from each other on the street, not too far from where King was a pastor. The first one on the left is to honor Jefferson Davis, erected in 1942 by the Daughters of the Confederacy. And across the street is a memorial honoring the Selma to Montgomery March that happened in 1965 and where Dr King gave his speech. And so I thought it was very interesting that these two narratives basically coexist with each other in the same place and I thought of it as a metaphor for our society.”

His observation, the old narrative and the revealing narrative, he notes suggests a power dynamic between current rhetorical worldviews in America.

“You see one narrative is aging but it’s still there, then another one that’s new and is getting a lot more attention. But the one that’s aging still has a lot of influence on society while the other is growing.”

He then went on to explain his frame for understanding the relation with these narratives. Defining rhetoric as “a series of communicative practices grounded in shared cultural knowledge,” he goes on explain the concept of rhetorical presences, or “the movement of the Black rhetorical presence – either the Black subject or features associated with Black rhetoric – for the Black community to the white community.” Crossover itself is a term he derived from music, where a popular R&B song crosses over into pop charts, the song becoming more heard and more “accepted” but also losing some of its cultural essence.

“Like with the example of Motown, they had to change their music in order to get more wider acceptance with a wider audience, and so this idea is that this happens when black elements of the black rhetorical presence crosses over into the mainstream. It is reinterpreted so to fit into the consumption of white taste.”

Who speaks the narrative then become important. Burrows labels the act of white people narrating about Blacks while ignoring racism as whitesplaining, while Afroplaining is the act of “reaffirming the existence of Blacks through direct and urgent narratives.” To Burrows, there is a cyclical dynamic between the two narrations, Afroplaining always in response against the appropriation of whitesplaining.

He goes on to elaborate on an example of whitesplaining, the revisionist narrative. Burrows asserts that it usually occurs when Black enter into positions of power, the revision itself stating the Blacks lack the mental knowhow to run things. Blacks are then portrayed as incompetent usurpers who are pulling whites from the “good ‘ole days.” Afroplaining then comes in response with the argument that when success occurs with Blacks, “white racism dismantles Black accomplishments because they threaten white narratives.” Burrows further points to Black historians like W.E.B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction and John Hope Franklin’s From Slavery to Freedom as strong examples for Afroplaining, as these working challenged the dominating white narrative by linking Black history to American history.

Towards the end of his talk, Burrows discusses how whitesplaining and afroplaining continue in current contexts, naturally pointing to the syllogisms surrounding BlackLivesMater. Whitesplaining responded with “All lives matter” and “Blue lives matter,” to which afroplaining put together the enthymeme of “All lives matter. Black people have lives. Thus, Black lives matter.”

Burrows ended his talk pointing to the continuation of these narratives in conversations like “The 1619 Project” and the Trump administration’s strangely published “The 1776 Project,” and that we must continue to dismantle whitesplaining narratives if we are to achieve any sort of racial equity.