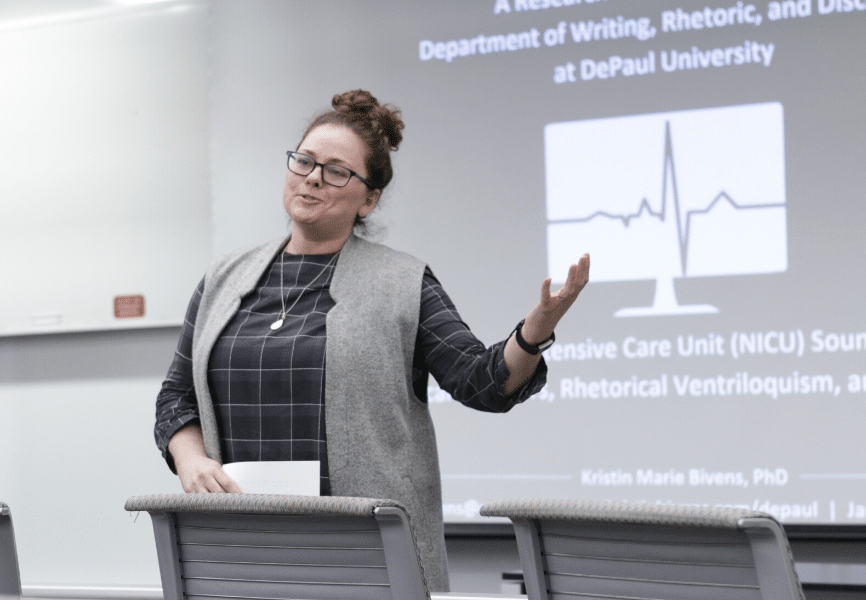

On January 22, the WRD Department hosted Dr. Kristin Bivens for the quarterly Writing & Rhetoric Across Borders Speaker Series. Dr. Bivens is a medical rhetorician and professional communication scholar. She teaches writing at Harold Washington College as an Associate Professor of English and is a member of the City Colleges of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB).

The morning’s workshop first introduced participants to “activist syllabi” and shared multiple resources for making classroom syllabi and other course materials more accessible. Some of these included:

- Using style headings;

- Incorporating alternative texts and image descriptions; and

- Soliciting both formal and informal feedback from students.

The evening research talk moved the focus from the classroom to the NICU (The Newborn Intensive Care Unit) to take a closer look at how sounds influence care and action, some of the findings of which are discussed in her article “A Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) Soundscape: Physiological Monitors, Rhetorical Ventriloquism, and Earwitnessing”

We got the chance to catch up with Dr. Bivens 1:1 following her workshop and speech to give readers a little more insight into her practices not only as medical rhetorician, but as a researcher, an instructor, and a writer.

So based on your bio and your website you wear a lot of hats! “Medical rhetorician, technical and professional communication scholar, associate professor” and so many more. Can you tell us more about that first one, “medical rhetorician?”

The rhetoric of health and medicine is a [subfield] of the rhetoric of science and is also a field right underneath rhetoric in general. So for those that do what I do, which is basically investigate communication within healthcare contexts, (e.g. written communication, spoken communication, etc.), there is an excellent [Rhetoric of Health and Medicine] Wikipedia page that was put together by Amy Koerber that addresses what is medical rhetoric, what are medical rhetoricians, and what questions are they concerned with.

For my [research questions] generally, I try to go to an impactful common denominator that might be underrepresented. The first big [research project] I ever did had to do with the ways nurses communicated with parents and other caregivers of pre-mature babies.

Why? I would contend that pre-mature infants are the most vulnerable population in any society, and they’re most at risk for a whole bevue of problems. And so when I looked in neo-natal intensive care units, I was concerned with how information was communicated and how that info circulated from experts– like health care clinicians, nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists– to non-experts like parents. There’s no correlation, and this is something that medical rhetoricians are concerned with. There’s no correlation between actual literacy and health literacy.

There’s a lot going on [in medical rhetorics], and the questions are primarily concerned with, I think, expertise and information moving from experts to non-experts.

“Designing Syllabi for Diverse Student Users: Content and Access”

At your workshop, the group spoke about accessibility and how to begin integrating more accessibility-minded practices into your “workflow.” Can you tell us a little bit about how you went about deciding what to start doing and when?

I wanted to draw upon any skills that I already had. Since I have a background in technical communication and style sets (or styling headings), using those style sets was something I had done on most things I had written, but since I started incorporating accessibility, I wanted to make sure those hierarchies of information for screen readers were in place on my syllabus, on my assignments, on any pdf really. So I started with what I knew.

A lot of accessibility work, as you said, is reactive, so how do you stay on top of trends and developments?

(laughs) Twitter.

There are scholars devoted to accessibility, and they’re on Twitter, and they’re regularly posting about accessibility. So staying on top of those trends, that’s one way to do it. I retweet not necessarily to endorse, but to remember, to archive.

Number two: the trends are sometimes dictated by lawsuits and so following for example WebAIM.org… they’ll often put out news on accessibility. But prioritize. And know you’re never really gonna be done.

For those who weren’t or aren’t able to come to your workshop and your talk, what is the one big thing from each you would want them to walk away knowing?

One takeaway from the workshop would be prioritize one or two things to integrate into your workflow. If you need help, seek out the help through your learning access center or whatever resources you have available to you. It’s easier to start from the beginning to design the information with [accessibility] in mind, than to ignore it, because the last thing you want to do is cut off opportunities for your students to learn.

For the research talk, I think the takeaway is that… sounds shape what we do. It’s synesthetic. We feel when we hear things. We feel it tactile-ly. It’s not just sound, so think of that in your digital composition process, whether that is recording a podcast for class or how-to instructions. Think about the aural, or the hearing, or the sonic properties of what you are trying to create.

What advice do you have for current writing students or writing faculty?

I remember once having a conversation with a senior scholar in technical and professional communication. And I said to her “I don’t think writer’s block is a thing,” because I don’t. And she said “Some of us are just perfectionist.” That’s true.

Cheryl Glenn, who teaches at Penn State, said there’s two kinds of theses/dissertations: Signed and unsigned. If we accept that writing is revision, that revision is the biggest, most challenging, most important part of the writing process, then we need to know the work we write today can very easily be changed tomorrow. I mean not once it goes to print, I’m not saying be careless. What I’m trying to say is, if you cannot write another word, take a nap, get a good night’s sleep and move from your focus mode to your diffuse mode of thinking.

And remember what the actor Edie Falco from the TV show the Sopranos said… “You know, Ton’. More is lost [by indecision], than wrong decision.” In other words, write the words. Write the phrase !rite the paragraph. See if it works, try it on, you’re not etching it into stone. Delete it, and put it in a file that says “Stuff I Spent A Lot of Time on but I Can’t Bear to Part With” and then it’s still there if you need it. That, and do not undervalue the role of topic sentences in a paragraph. When you get lost, find your way back to those topic sentences, and you’ll find your way back to your big ideas.